Personhood

by Eliza Erdrich

“The arrogance of English is that the only way to be animate, to be worthy of respect and moral concern, is to be a human.” - Robin Wall Kimmerer in Braiding Sweetgrass.

In my language Ojibwe, and related Anishinaabe languages such as Potowatomi which Robin Wall Kimmerer speaks, ‘animate’ is a category that includes plants, animals, rocks, water, and features like bays. They are beings with agency, subjects rather than objects, in both grammar and relationship to humans, their own kind of People. The same is not true in the dominant Christian ideologies of colonizing powers, which promote a view of the world with a hierarchy that marks humans as separate and above Nature. In this logic, people have agency and rights, and things don’t, and only humans are people (and often criteria for “people” has been narrowed further to only white-male-Christian humans). Any exemptions to this rule can only be expressed by extending human characteristics or descriptors, such as calling ships the feminine “she”, rather than acknowledging the inherent person-ness of a non-human. This exclusionary view is seen in legal systems and policies toward Nature in settler states, all of which focus exclusively on the benefit or convenience of humans (and again, not even all humans, all the time). Conflicts (ideological, legal, or literal), between the colonialist human-centric mindset and broader Indigenous definitions of person are strewn throughout history and the present day. Therefore, the concept of “personhood” as a subject of study and discussion has a place in many layers of Indigenous studies, from linguistic to legal. This keyword essay will focus mainly on the legal definitions and applications of the term, rather than the epistemological or moral dimensions of it, although they are often entwined.

What is legal personhood?

In Western legal practice, “Personhood” is defined as having the right to take certain legal actions, such as suing, being sued, and entering into contracts. Humans are considered “natural persons”, whose personhood comes naturally with birth, while any other entity that needs to have those same legal rights is considered an “artificial person” and must have its personhood conferred to it by an outside entity (Cornell Legal Encyclopedia, 2024). Thus, the legal system, and by extension the colonial system it is rooted in and the capitalist system it functions on behalf of, have hegemony over who and what gets recognized as a “person” and therefore has any legal power. Within these systems, artificial personhood is most often given to businesses and corporations, and those corporations use that status to their benefit. For example, lobbying in America is considered an exercise of corporate entities’ constitutional right to free speech, the speech being money (Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 2010). Whereas the natural world and natural entities are considered objects and resources, without rights or legal power of their own.

This concept can be compared to Indigenous relational philosophies or legal traditions in regards to the natural world, some of which consider many things other than human to have a personhood that is not reflected within Western legal practice. For example, the Anishinaabek(g) ‘natural law’ of ‘Enendagwad’ discussed by Anishinaabe scholar Deborah McGregor. This concept of law is shaped by Anishinaabek(g) ontologies, and governs human relationships with and responsibilities to other Orders of beings, as well as other humans. Within a framework like this, non-humans are equal parties, persons, with their own responsibilities in their relationships to humans (McGregor, 2013, 72).

Personhood and Nature

One space the difference between concepts of personhood can be felt distinctly is in policies around Nature, as such, Legal personhood has taken on an important role in environmentalism, especially with the rise of ‘rights of Nature’ legal initiatives. Efforts in the pursuit of the ‘rights of Nature’ have been influenced on many levels by Indigenous organizations, and philosophies. These efforts often center around either establishing legal rights for natural entities within constitutions, or establishing them individually through recognition of legal personhood. The ‘rights of Nature’ concept began with Christopher Stone, who first analyzed the legal concept in his 1972 article Should Trees Have Standing? Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects. By conferring personhood to natural entities such as plants, animals, and bodies of water, humans can then use those legal rights to protect them, usually by suing other entities that are threatening or harming them on their behalf (Morris, Ruru, 2010). Many countries and governments have adopted ‘rights of Nature’ laws, and recognized the legal personhood of certain natural entities in recent years. Of these, many of the biggest and most impactful moves have been driven by Indigenous groups, or adopted by Indigenous legal authorities.

Legal personhood cases and Indigenous ontologies/sovereignty

New Zealand is a country in which Indigenous influence on the matter of legal personhood for natural entities has had a pronounced effect. In a 2010 article, Maori scholars Jacinta Ruru and James Morris promote the framework of legal personhood as a way to protect New Zealand's rivers, and to exercise Indigenous relationships to water and Indigenous sovereignty. Ruru and Morris argued that “The legal personality concept aligns with the Maori legal concept of a personified natural world. By regarding the river as having its own standing, the mana (authority) and mauri (life force) of the river would be recognised.” (Morris, Ruru, 2010, 50). And, in 2017, the Whanganui river was indeed recognized as its own legal entity in the Te Awa Tupua/Whanganui River Claims Settlement Act. New Zealand has so far recognized rights of the natural environment in two cases: the Whanganui river, and Te Urewera, a rainforest ecosystem that used to be a National Park. In 2014 the Te Urewera rainforest ecosystem was declared “a legal entity, and has all the rights, powers, duties, and liabilities of a legal person” (Te Urewera act, 2014, section 11.1) with a board that was ‘created in order to act on behalf of, and to “provide governance”’ to Te Urewera, but also importantly and explicitly given reign to govern according to Tūhoe principles (Tănăsescu, 2020).

But New Zealand is not the only country to take such moves. In 2008 Ecuador, as a part of the restructuring and re-writing of its constitution, was the first country to include protection of ‘rights of Nature’ for “pachamama”, mother earth. This element of the new constitution was supported and pushed by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) alongside other amendments and rights that pushed for stronger Indigenous authority in general (Tănăsescu ,2020). Bolivia adopted similar provisions for the rights of Nature in its own constitution in (Racehorse, 2023). In regards to individual entities legal personhood, in 2017 in Colombia the Atrato River acquired rights, and in India both the Ganges and Yamuna rivers have been recently declared legal persons. And in Australia the Yarra River has been recognized as “one living and integrated natural entity” in the Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017 (Clark et al, 2019). So far, the majority of natural features that have received personhood status have been bodies of water, specifically rivers.

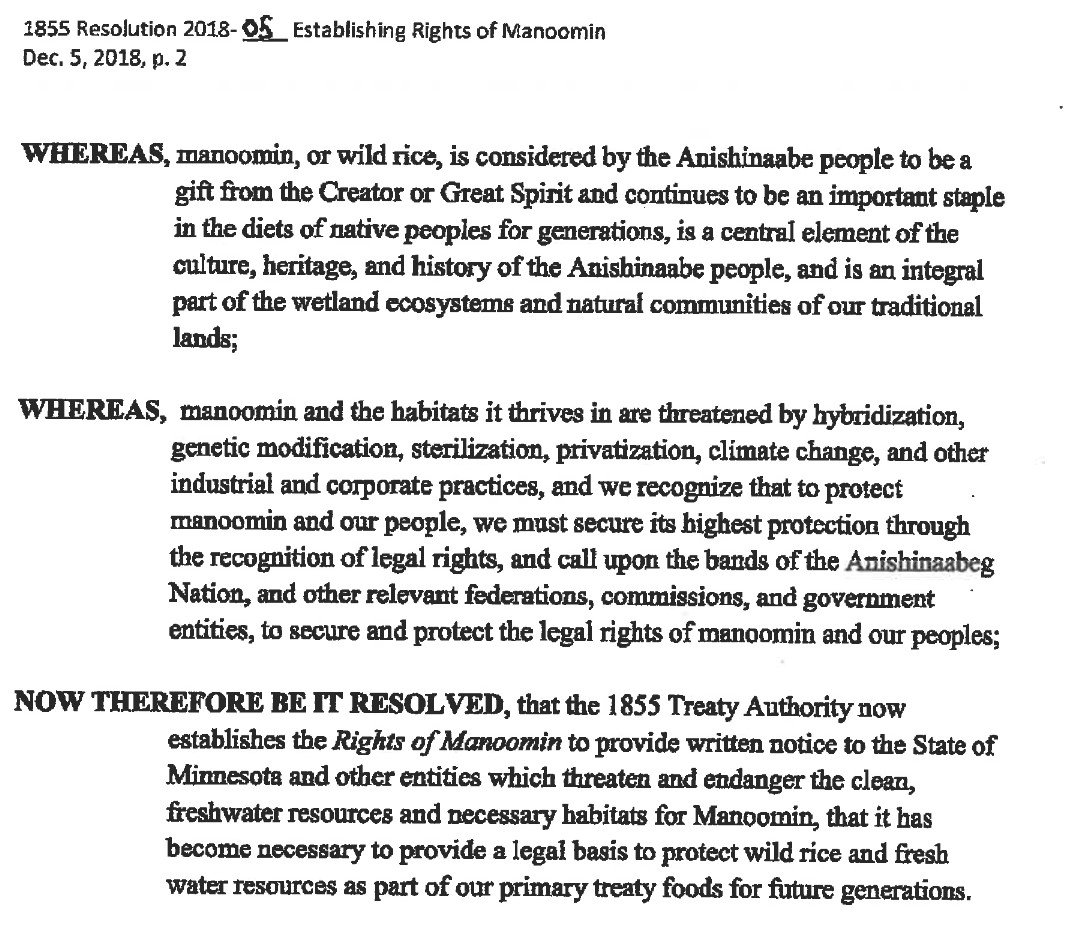

Within America, many tribal governments have made moves toward rights of Nature such as recognizing the legal personhood of rivers, or enshrined their own traditional natural law in their constitutions. For example, in 2019 the Yurok tribe passed a Resolution Establishing the Rights of the Klamath River, recognizing its Legal personhood, as one step in their very long fight to restore and protect the river. As of 2024, four hydroelectric dams have been removed from the river, allowing it to run reely for the first time in over a century, one of the rights guaranteed to it in the resolution by the tribe (Siskiyou news, 2023) (State of California, 2024). In my home state of Minnesota, The White Earth Band of Ojibwe passed Resolution No. 001-19-009 (Dec. 31, 2018) which recognized the rights of Manoomin (wild rice) as a legal entity, this was the first time these rights have been extended to a particular plant species, rather than an ecosystem or Nature in the general sense (Racehorse, 2023). In 2021, the legal rights of Manoomin were exercised in Manoomin v. the Minnesota Department of Natural resources, when Manoomin sued the MN DNR in White Earth Tribal Court over its approval of the Enbridge line 3 oil pipeline, which endangered waters where it grows (Belinski, 2023). Below I have included an example of the language used in the “Resolution on the Rights of Manoomin”, which I find to be exemplary of this kind of recognition of rights and personhood, as adopted by tribal governments or influenced by Indigenous groups.

Limitations and possibilities

Legal personhood is considered by some Indigenous scholars as a damage control measure, a placeholder rather than a true exercise of their own natural laws or ontologies. And, though personhood has power within a Western legal framework, it still has limits within that system. This has been borne out by the sometimes lackluster results of attempting to enforce these rights. Still, there are possibilities and paths forward through Legal personhood and ‘rights of Nature’ initiatives.

In American legal cases there is a recurring theme of tribes, municipalities, or individuals attempting to enforce the rights of Nature, and the law or court being found to operate outside of its jurisdiction (Racehorse, 2023). Tribes' ability to enforce rights of Nature laws or legal personhood rights are curtailed by the Montana v US case, saying tribal law cannot be enforced on non-members unless they are on reservation land. In the case of Manoomin v. the MN DNR, the Tribal court eventually ruled that Manoomin’s rights did not apply to off-rez activities based on the Montana precedent (Belinski, 2023). Even though the case was brought before tribal court, the overarching American legal system prevented the effective exercise of Manoomin’s rights, however there is some hope in the possibility of similar lawsuits going a different way in the future, perhaps with an argument of off-rez activity’s effects on-reservation, in which case Legal personhood for natural entities could provide a powerful route for exercising Tribal sovereignty (Racehorse, 2023).

Returning to New Zealand and Te Urewera, Maori researcher Dr. Mihnea Tănăsescu argues that the Te Urewera act is, among other things, a compromise that avoids placing land ownership or full political authority in either the Crown or Tūhoe hands, and thus restrains Tūhoe legal authority and capacity to enact their relationship with Te Urewera. However, she also comments that Tūhoe ontology, and relational view of Nature, has space to be practiced within the framework of the act. She considers Te Kawa, the management plan that the governing board of Te Urewera has proposed, to be “quite explicit in circumventing the notion of rights per se, as well as shifting the focus away from the human as the model of legal status and towards as yet unexplored possibilities.” (Tănăsescu, 2020, 448).

Along a similar vein, Aboriginal Australian scholar Virginia Marshall argues that ‘rights of Nature’ efforts to give legal personhood to bodies of water, and other natural entities, are at their heart, an environmentalism driven replacement for human centric property based laws, and still build upon an ontology that places humans and Nature as separate things rather than Indigenous ontologies (Marshall, 2019). Personhood further divides, by individualizing natural features which are, in reality, continuous parts of the world around them. She also observes that the implementation of Legal Personhood can go directly against Indigenous interests, or at least those of Aboriginal people in Australia, and that their political voice can be drowned out by environmental policy groups. In Removing the Veil from the ‘Rights of Nature’: The Dichotomy between First Nations Customary Rights and Environmental Legal Personhood. Marshall states her perspective concisely, saying: “As the oldest surviving cultures in the world, exercising Indigenous law, with thousands of years of knowledge in land and water management, why would Indigenous communities want to replace our legal system with legal personhood?” (Marshall, 2019, 236)

Conclusion

While colonial legal systems may have hegemony over the legal definition of Personhood, Indigenous people have their own knowledge and definitions that refute that understanding, and are making that legal system bend closer towards them. The artificial personhood offered by the legal system often resembles, or is influenced in its exercise by, the limited and dependent type of sovereignty afforded for Indigenous nations. However, the methods of enforcing the rights of these legal entities provide avenues to exercise tribal sovereignty in the US, and practice traditional legal responsibilities or relationalities elsewhere, such as through the Te Urewera act. Ultimately, such things are ideally stop-gap measures, damage control, to pave the way for more full exercising of traditional relationships and responsibilities. Or as doctor Robin Wall Kimmerer puts it:

“Maybe a grammar of animacy could lead us to whole new ways of living in the world, other speciese a sovereign people, a world with a democracy of species, not a tyranny of one—with moral responsibility to water and wolves, and with a legal system that recognizes the standing of other species. It’s all in the pronouns.” - Pages 57-58, Braiding Sweetgrass.

Bibliography

Belinski, Anna. "Minnesota Dep’t of Nat. Res. v. Manoomin," Public Land & Resources Law Review: Vol. 0, Article 3. (2023)Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/plrlr/vol0/iss22

Clark, Cristy, Nia Emmanouil, John Page, and Alessandro Pelizzon. “Can You Hear the Rivers Sing? Legal Personhood, Ontology, and the Nitty- Gritty of Governance.” Ecology Law Quarterly 45, no. 4 (2019): 787–844. doi:10.15779/Z388S4JP7M.

California, State of. “Klamath River Dams Fully Removed Ahead of Schedule.” Governor of California , October 2, 2024. https://www.gov.ca.gov/2024/10/02/klamath-river-dams-fully-removed-ahead-of-schedule/.

CITIZENS UNITED v. FEDERAL ELECTION COMM’N ( No. 08-205 ) , Legal Information Institute (SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES 2010).

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass : Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. 1st ed., Milkweed Editions, 2013.

Marshall, Virginia. “Removing the Veil from the ‘Rights of Nature’: The Dichotomy between First Nations Customary Rights and Environmental Legal Personhood.” Australian Feminist Law Journal 45 (2): 233–48. (2019) doi:10.1080/13200968.2019.1802154.

McGregor, Deborah. "Indigenous Women, Water Justice and Zaagidowin (Love)." Canadian Woman Studies 30, no. 2 (2013): 71-78. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/Indigenous-women-water-justice-zaagidowin-love/docview/1806416896/se-2.

Morris, James D. K. and Jacinta Ruru. “Giving Voice to Rivers: Legal Personality as a Vehicle for Recognising Indigenous Peoples’ Relationships to Water?” Australian Indigenous Law Review 14, no. 2 (2010): 49-62.,

Martin, Jay A. “The Klamath River Has the ‘Legal Rights of a Person’ .” Siskiyou News, October 26, 2023. https://www.siskiyou.news/2023/10/26/the-klamath-river-has-the-legal-rights-of-a-person-a-yurok-tribe-resolution-establishing-rights-of-the-klamath-river/.

Racehorse, Vanessa. "Indigenous Influence on the Rights of Nature Movement." Natural Resources & Environment 38, no. 2 (Fall, 2023): 4-8. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/indigenous-influence-on-rights-Nature-movement/docview/2892800570/se-2.

Tănăsescu, Mihnea. "Rights of Nature, Legal Personality, and Indigenous Philosophies." Transnational Environmental Law 9, no. 3 (11, 2020): 429-453. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102520000217. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/rights-nature-legal-personality-indigenous/docview/2460993638/se-2.

The Parliament of New Zealand, Department of Conservation, Te Urewera Act 2014, edited 2019,https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2014/0051/latest/DLM6183601.html?search=ad_act__te+urewera____25_ac%40bn%40rn%40dn%40apub%40aloc%40apri%40apro%40aimp%40bgov%40bloc%40bpri%40bmem%40rpub%40rimp_ac%40ainf%40anif%40bcur%40rinf%40rnif_a_aw_se_&p=1

White Earth Reservation Business Committee and the White Earth Band of Chippewa Indians.“Rights of Manoomin.” 1855 Treaty Authority. (December 31, 2018.)

Wex. “Legal Person.” Legal Information Institute. Accessed November 25, 2024. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/legal_person.